The Wakes is a museum in the Hampshire village of Selborne which was once home to the writer and naturalist, Gilbert White. Now a museum dedicated to Gilbert White, some rooms on the upper floor have been allocated to the Oates family; Frank Oates the African explorer and naturalist, and his nephew, Captain Lawrence Oates. Known for his heroism and courage, three rooms here tell the story of Oates and his role on the ill fated trip to the Antarctic.

- Sarah Nash

- Last Checked and/or Updated 15 December 2021

- No Comments

- England, Exhibitions

There are only three rooms in the museum dedicated to Captain Lawrence Oates, but the experience of his presence there is nonetheless very powerful. After a visit to the rest of the museum, which looks at the life of Gilbert White and his study of naturalism, then Frank Oates and his explorations and studies of nature, to move to the life of Oates seems incongruous, until you make the connection that it is again about the power of nature, albeit in a different capacity.

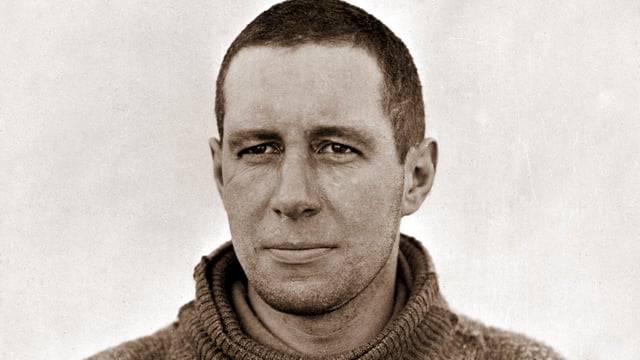

Born in London in 1880, Lawrence Edward Grace Oates was born into a wealthy family, his birth recorded into a diary kept by his mother, Caroline, with the words, ‘baby is born at 6.20’. This diary is on display in the museum, propped open and resting on a silk scarf. He was an unhealthy child, suffering from bad lungs which got worse when it was cold and damp.

The first gallery establishes the character of the man through his delight in all sports, his fairly mediocre record at Eton College, which he had to leave early due to pneumonia, and his time spent at home with horses. There is a letter on display which he wrote as a small child in 1887, in large, but rather elegant copperplate handwriting.

He was determined to join the army, and not academic enough to apply to Sandhurst, he joined the Militia in 1898. The Boer War broke out the following year and he was able to get a commission with the 6th Inniskilling Dragoons. In the Boer War in South Africa Oates got the nickname “No Surrender” Oates for his refusal to surrender to a much superior Boer force, and earned himself a recommendation for the Victoria Cross. There are transcripts of his letters home from South Africa, complaining about the food and asking for tobacco to be sent to him, but saying that he was enjoying himself immensely.

A gunshot wound in the left thigh left him with a permanent limp, and the left leg shorter than the other. He remained with the army, being promoted to Captain in 1906 and serving in India, Ireland and Egypt. By 1909 he was getting bored, and from service in India, on impulse he wrote to Robert Scott and asked to join the planned expedition to the Antarctic, offering to contribute £1,000 to the expedition’s funds. The transcript of his letter to his mother is on his display, ‘confessing’ that he had volunteered to go on the mission and weighing up the pros and cons of his decision. He was chosen because of his vast experience with horses although, surprisingly, did not get to choose them and when he first encountered them he described them as ‘a wretched load of crocks.’

The expedition left Cardiff in the Terra Nova in June 1910.

In the second gallery, the sounds of an Antarctic blizzard echo around the pale blue walls, immersing the visitor into the freezing cold of the approach to the South Pole. Poignant artefacts from the Terra Nova are on display, the Royal Yacht Squadron burgee which was flown from the masthead, a life belt, a caricature drawn of Oates who was known as ‘the soldier’ and a letter from Oates to his mother, written from the ship.

Scott’s team set off from base camp on the 900 mile journey in November 1911. Some of the clothing and equipment displayed in the gallery leaves modern visitors aghast. Scott’s balaclava looks pathetically thin and inadequate against the elements, the sledge used to pull equipment looks rickety and fragile, one of Oates’ snow shoes seems to be made of rattan. A figure in polar clothing leans forward into the wind against a backdrop of snow covered mountains with little protection against the elements compared to cold weather clothes of modern times.

Despite all of Oates’ efforts to care for them, the ponies all died, leaving the team dangerously dependent on dogs and their own strength. But Oates’ willingness to do all that was asked of him meant that Scott had no hesitation in choosing him as one of the five men set to reach the actual Pole. On a packing case is an assortment of slides taken by the expedition photographer,Herbert Ponting, which visitors can look at. They show scenes of life during the expedition, the Terra Nova stuck in ice, Oates with his ponies, members lying on their wooden bunks surrounded by their kit.

The team reached the South Pole in January 1912, only to realise that the Norwegian flag already there meant that Amundsen had beaten them in the race. Dejected, the team turned homeward. The weather conditions turned against them, they expected dog-teams failed to meet them and there was a shortage of fuel. By now, Oates’ old Boer war wound was troubling him and his feet were suffering through frostbite. He believed that his condition was slowing down the others, and in an attempt to save his colleagues he stepped out of the tent saying quietly, “I am just going outside and I may be some time”, words which resonate with all brought up in the belief of the power and heroism of the British Empire.

The expedition never returned and a search party found the bodies of all but Oates, lying in the tent, surrounded by their diaries and personal effects, just 11 miles from the nearest depot. The ‘Sutton Collection’ is on display – items found by the search party and brought back. These include cans of pemmican, cutlery, a pewter dining set and a small case which belonged to Oates. Rusted and aged, they bring the distressing reality of that event to prominence; this was not just an expedition in history books, this was tragically real.

A letter from Dr Wilson which was found next to his body in the tent, addressed to Mrs Oates and telling her how bravely Oates had sacrificed himself for them, despite knowing that he is going to die too, is a heartbreaking read. On a wall is a small handwritten receipt from Dr Jaegers of Regent Street for clothes ordered by Mrs Oates for clothes for Lawrence to be sent out to him in the Antarctic. He had already been dead for several months by the time she did so.

The exhibition ends with a look at the benefits that the expedition provided to science, which was their primary objective for going. They took samples and photographs which still provide scientists with insights today. An area for kids to dress up in polar clothing and learn about penguins tries to lighten the mood, but the exhibition remains with you even once you have stepped outside into the beautiful grounds of The Wakes.

Read about visiting the rest of The Wakes and the life of Gilbert White in his Selborne home >>

Opening Hours

4 January – 17 February, Friday to Sunday, 10h30 – 16h30

18 February – 22nd December, Tuesday – Sunday, 10h30 – 16h00

Ticket Prices

Adult: £12

Child (5-16 yrs): £5,

Children under 5: free

Family tickets available

Facilities

The gardens and ground floor are accessible to wheelchairs and pushchairs. There is no lift to reach the top floor.

Free parking is available next to the Church or further down the High Street.